|

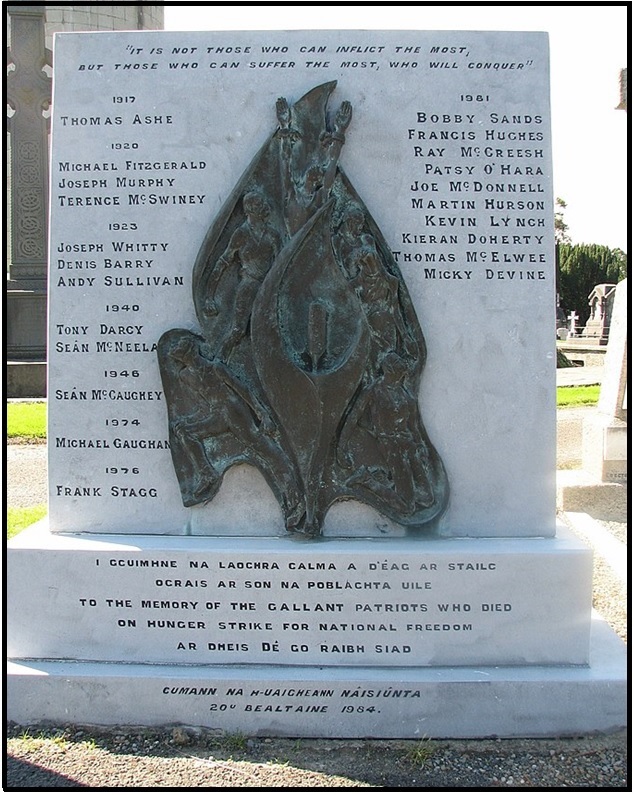

Between 1917 and 1981 , 22 Irish Republican POW’s

died on hunger-strike.

Thomas Ashe, Kerry, 5 days, 25 September 1917

force fed by tube , died as a result).

Terrence MacSwiney, Cork, 74 days, 25 October 1920.

Michael Fitzgerald, Cork, 67 days, 17 October 1920.

Joseph Murphy, Cork, 76 days , 25 October 1920 .

Joe Witty, Wexford , 2 September 1923.

Dennis Barry, Cork, 34 days, 20 November 1923.

Andy O Sullivan , Cork, 40 days, 22 November 1923.

Tony Darcy, Galway, 52 days, 16 April 1940.

Jack ‘Sean’ McNeela, Mayo, 55 days, 19 April 1940.

Sean McCaughey, Tyrone ,22 days, 11 May 1946

(hunger and thirst Strike).

Michael Gaughan, Mayo , 64 days, 3 June 1974.

Frank Stagg, Mayo , 62 days, 12 February 1976.

Bobby Sands, Belfast , 66 days, 5 May 1981.

Frank Hughes , Bellaghy (Derry) , 59 days, 12 May 1981.

Raymond McCreesh , So. Armagh , 61 days, 21 May 1981.

Patsy O Hara , Derry , 61 days, 21 May 1981.

Joe McDonnell , Belfast , 61 days, 8 July 1981.

Martin Hurson , Tyrone , 46 days, 13 July 1981.

Kevin Lynch, Dungiven (Derry) ,71 days, 1 August 1981.

Kieran Doherty , Belfast , 73 days, 2 August 1981.

Tom McIlwee , Bellaghy (Derry) , 62 days, 8 August 1981.

Micky Devine , Derry , 60 days, 20 August 1981.

The hunger strike is part

of a very ancient Irish tradition, although it seems that James

Connolly was the first to use it in 1913 as tool of political

protest in 20th century Ireland. From 20 September 1917, Irish

internees used the hunger strike as a means of trying to secure

their rights from an implacable enemy.

Thomas Ashe, former principal of Corduff National School,was

the first to die after an attempted force-feeding.

Fasting as a means of

asserting one’s rights when faced with no other means of obtaining

redress is something that has been embedded in Irish culture from

ancient times. Even when the ancient Irish law system,

the Laws of th Fénechus, which we popularly called

the Brehon Laws from the word breitheamh, a judge, were

first codified in AD 438, the law relating to

the troscad, or hunger strike, was ancient.

The hunger striker gave

notice of their intent and, according to the law tract Di

Chetharslicht Athgabhála, if the person who is being fasted

against does not come to arbitration, and actually allows the

protester to die, then the moral judgement went against them and

they endured shame and contempt until they made recompense to the

family of the dead person. If they failed to make such amends, they

were not only damned by society but damned in the next world. They

were held to be without honour and without morality. The ancient

Irish texts are full of examples of people fasting to assert their

rights and shame powerful enemies into accepting their moral

obligations. St Patrick is recorded to have done so according to

the Tripartite Life of St Patrick. And, in

the Life of St Ailbe, we found St Lugid and St Salchin,

carrying out ritual fasts to protest.

Even

King Conall Dearg of Connacht fasted when he found his

rights infringed. And the entire population of Leinster fasted

against

St Colmcille when he rode roughshod over their rights. The

poet Mairgen mac Amalgado mac Mael Ruain of

the Deisi fasted against another poet Finguine over an act

of perceived injustice. The troscad continued in Irish law

throughout the centuries until the English conquests proscribed the

native law system and foisted English law on Ireland through a

series of Acts between 1587 and 1613. Nevertheless, individual fasts

against the cruelties of the English colonial administration are

recorded several times over the subsequent years…

back to top

The hunger

strikes 1917- 1920

BY --- Patrick McGlynn

Of

those who died on hunger-strike between the Easter Rising 1916 and

the Treaty of 1921, Thomas Ashe and Terence MacSwiney are by far the

best known. In the first two parts of this five-part series, Patrick

McGlynn detailed the events surrounding their deaths and this week,

in part three, covers the deaths of two other IRA Volunteers who

died during the same hunger-strike as Mac Swiney. That

hunger-strike, in fact, was the longest ever hunger-strike without

force-feeding.

This

article also records the deaths of four other Volunteers who died

during those years as a direct result of having taken part in prison

fasts. The final two parts of the series will cover the IRA

hunger-strikers who died in Free State jails in the twenties and the

forties, and the two who died in English jails in the seventies. The

many parallels between today's hunger-strikers and those of previous

campaigns clearly show the historical precedent of the current

life-or-death struggle in the H-Blocks against the attempted

criminalization of the republican war effort.

There were three years between the death of Thomas Ashe in

September 1917 and the deaths on hunger-strike of Terence MacSwiney,

Michael Fitzgerald and Joseph Murphy, in October 1920. However,

during the intervening years there were several hunger- strikes by

republican prisoners in jails in Ireland and Britain. The prisoners

who had been on hunger- strike with Thomas Ashe in Mountjoy jail in

Dublin were granted political status after his death. But, at

Christmas 1917, they were moved to Dundalk jail where they found

that all the rights won in Mountjoy were taken away and the attempt

to criminalize them commenced once again. Early in 1918, Austin

Stack and the other political prisoners in Dundalk jail again

resorted to hunger-strike to regain the rights which Ashe had won,

and they were quickly joined in their action by the IRA prisoners in

Cork jail.

Terence MacSwiney, who was to die on hunger-strike in October 1920,

was in Cork jail at that time and warned his comrades to take the

protest seriously. 'This may be a fight to the death' he told them,

"and we must stick to it as long as possible." The British

authorities were extremely nervous, fearing the consequences of

another death like that of Ashe. Five or six days into the fast, one

of the Cork prisoners collapsed. The prison doctor, in panic,

recommended the prisoners be immediately released. They were all

served with notices to return within a month. But the notices, of

course, were ignored. As a result of the hunger-strike in Cork —

although it was of short duration — the health of one of the

prisoners, Seamus Courtney, Passage West, (O/C Fianna Eireann,

Cork) , was ruined and he later died on July 1921 . The funeral

of hunger-striker Michael Fitzgerald in Cork, October 1920 22nd 1918

and was buried in Passage West. Of the Dundalk prisoners, who also

were all released around the same time, Aidan Gleeson, of Liverpool,

entered the Mater hospital in Dublin where he died, as a result of

the hunger-strike, shortly after his release.

By

1920, the Black and Tan War was at its height and more and more IRA

men were imprisoned. On April 5th 1920, sixty republican prisoners

again resorted to the ultimate weapon of hunger-strike in support of

their demand to be treated as prisoners-of- war. Night and day,

large and anxious crowds. gathered outside the jail and alternated

between saying prayers and singing rebel songs. It was not yet

popularly realized in. Ireland that a hunger-striker could survive

for several weeks. Parents of the hunger-strikers were given special

visits by the authorities, who hoped that they would persuade the

young men to take food. But instead, the relatives gave added

support to the prisoners.

After seven days of the hunger-strike, on April 12th, a general

strike was called in Dublin by the Irish Labour Party and the trade

unions in support of the prisoners. The strike was totally

effective. On April 14th, on the third day of the general strike and

the tenth day of the hunger-strike, the authorities gave way and

announced that the prisoners would be released unconditionally. This

took place on April 20th. However, as a result of the hunger-strike,

Patrick Fogarty of Clontarf, Dublin, had died in hospital on April

18th, and was buried in Glasnevin cemetery. And, a month after the

end of the hunger-strike, on May 14th, another released prisoner,

Francis Gleeson, of Fairview in Dublin, died in the Mater hospital

from the after-effects of the hunger-strike. On August 11th 1920

another hunger- strike began in Cork jail, when sixty IRA prisoners

began a fast in support of their demand for political status. It was

this hunger-strike which Terence MacSwiney joined, on his arrest the

following day; and MacSwiney died in Brixton prison, to where he had

been deported. Two other IRA Volunteers, Michael Fitzgerald and

Joseph Murphy, died on the same hunger-strike in Cork jail.

Michael Fitzgerald, from Fermoy in County Cork, joined the

Volunteers in 1914 and was appointed O/C of the Cork Second

Command's Fourth Battalion. Following a raid on an RIC barracks at

Araglen, on Easter Sunday 1919, Fitzgerald was captured and

sentenced to two months' imprisonment, all of which he spent in

solitary confinement. After his release he again, became active in

the IRA. On September 7th 1919, he and many other Volunteers were

rounded up after an attack on British troops in Fermoy, in which one

of the enemy was killed. Fitzgerald was charged with murder, but no

jury could be empaneled to try the case, so that it was continually

put back while he remained in custody. On August 11th of the

following year, Michael Fitzgerald began the hunger- strike in Cork

jail with the other prisoners. During the weeks that followed, the

British released or transferred many of the hunger-strikers until

only eleven were left of the original sixty. During September and

October, as the hunger-strikers deteriorated, crowds gathered daily

outside the jail to pray and sing hymns. World attention, however,

was focused on Terence MacSwiney's lonely struggle in Brixton

prison.

For

sixty-seven days, Michael Fitzgerald endured the agonies of

hunger-strike until he died on Sunday 17th October 1920. On the

Monday night, Fitzgerald's comrades transferred his remains to the

Church of Saints Peter and Paul in Cork city, where a Requiem Mass

was said the following day. As the Mass was ending, British troops

saturated the area around the church and, with steel helmets and

bayonets fixed, forced their way to the altar by climbing over the

seats. An officer, with gun drawn, handed the priest a notice

stating that the authorities would only allow a limited number of

people to follow the funeral. In spite of this intimidation,

thousands of people followed the cortege on its way to Fermoy. And,

the!. £o| lowing day, Wednesday, mass' crowds gathered, despite

British roadblocks and searches, tor another Requiem Mass and the

burial in Kilcrumper cemetery. Late the same evening IRA Volunteers

returned to fire a farewell volley over their comrade's grave.

On

the following Monday, October 25th, a few hours after the death of

Terence MacSwiney, another of the Cork prisoners, Joseph Murphy,

died on his seventy-sixth day on hunger-strike. His body,

accompanied by IRA Volunteers and members of Cumann na mBan, was

brought through his native Cork city to the Church of the Immaculate

Conception. The following day, after Requiem Mass, the funeral took

place to St Finbarr's cemetery. It has been suggested, with some

authority, that the reason for the protracted length of this

hunger-strike (in which force-feeding was not used) was because the

prison authorities had secretly introduced some nourishment, mainly

in the form of egg white, into the prisoners' drinking water, and by

this means they had hoped to extend their own chances of breaking

the prisoners' resolve. In the event, it was some days after

Murphy's death before some concessions were made and the remaining

nine Cork prisoners ended their hunger-strike on the advice of the

acting-president of the Irish Republic, Arthur Griffith.

back to top

Hunger strike deaths in Free State jails 1920s to 1940s

Patrick McGlynn

The

end of the- Civil War came in May 1923 with the order on the

Republican side to dump arms. Nevertheless, thousands of republican

prisoners, men and women, were held for several months afterwards in

the most atrocious conditions in Free State prisons and internment

camps — most of them had not been brought to trial. In fact, it was

over a year later before the last of the internees were released.

There had been a short hunger-strike In Tintown concentration camp

at the Curragh as early as June 1923, and It was as a result of this

that Daniel Downey of Dundalk, County Louth, died on June 10th.

Although the hunger-strike had ended before he died, the short fast,

together with the brutal beatings and general Ill-treatment meted

out to the prisoners, proved to be fatal.

The major hunger-strike of the period, however, came In October

1923, by which time the republican prisoners had become very

impatient for release from conditions which had become almost

unendurable. This hunger-strike was started by more than four

hundred prisoners in Mountjoy, ten of them TDs, and it quickly

spread men and women prisoners in other jails and internment camps.

There were massive protests outside the prisons in support of the

prisoners. On November 20th, Commandant Dennis Barry, from

Blackrock, County Cork, died on hunger-strike in Newbridge Camp,

County Kildare. Two days later, Captain Andrew Sullivan of Mallow,

County Cork, died after forty days without food in Mountjoy. On

November 23rd, the hundreds of prisoners still on hunger-strike

ended their protest. Soon afterwards all the women prisoners and a

number of the men were released. Conditions for those remaining were

improved to some extent. Many of those on the hunger-strike had

their health irreparably damaged by the fast and many suffered

afterwards by taking food again without any medical supervision. One

prisoner, in particular, Joseph Lacey of Blackwater, County

Waterford, continued to decline after the end of the hunger-strike,

and died a month later on Christmas Eve 1923.

Hunger-striking had claimed another victim that year, John Oliver,

one of those who had taken part in the Connaught Rangers' mutiny in

India in 1920. He, with others, had gone on hunger strike In

Maidstone prison in England in 1922. They were brutally treated

during the course of the protest and forcibly fed in a particularly

torturous manner. After their hunger-strike the Maidstone prisoners

wore released, but John Oliver, totally debilitated by his

experience, contracted TB and died the following year.

It was almost twenty years before a hunger-strike was to claim the

life of another republican prisoner in a Free State jail, and by

this time it was a Fianna Fail government that was in office. The

proscribing of the IRA by the Fianna Fail government in 1939, soon

led to Free State jails filling once again with republican prisoners

in the 20s. The funeral cortege of IRA Volunteer Sean McCaughey

(Inset), passing along Dublin's O'Connell Street In 1946 In

Mountjoy, conditions were appalling and the republican prisoners

were constantly agitating for recognition as political prisoners. It

was eventually decided to begin a hunger-strike to this end, the

main demand being for free association.

On February 25th 1940, Tony D'Arcy, Sean McNeela, Thomas Grogan,

Jack Plunkett, Tomas MacCurtain and Michael Traynor all refused food

and began to hunger-strike. On March 1st, the republican prisoners,

including the hunger-strikers, were savagely beaten by warders,

backed up by Special Branch men, when they attempted to prevent

McNeela and Plunkett being removed to face trial before the military

court. In the event, McNeela was sentenced to two years and Plunkett

to eighteen months, on a charge of 'conspiring to usurp a function

of government' by operating a 'private' radio transmitter. (Sean

McNeela had been the IRA's Director of Publicity.)

On March 5th, Tony D'Arcy and Michael Traynor were sentenced to

three months' imprisonment for refusing to answer questions. They

had been arrested with others following a swoop on the Meath Hotel

in Dublin where a meeting of IRA O/Cs from around the country was

taking place, After being sentenced the four were transferred to

Arbour Hill and on March 27th were moved to St. Brian's hospital

next to the prison. They were joined there on April 1st by Tomas

MacCurtain and Thomas Grogan, both of whom were still awaiting

trial. (MacCurtain was charged with the shooting dead of a Special

Branch man, and Grogan with taking part in the Magazine Fort raid -

in which the IRA scooped almost all the Free State army's

ammunition, in 1939). On April 16th 1940, after forty-two days on

hunger-strike, Tony D'Arcy died. His last words were 'Jack, Jack,

Jack McNeela, I'm dying.' And McNeela, leaving his bed to go to his

dying comrade, collapsed on the floor. Tony D'Arcy had completed two

months of his three-month sentence when he died. Three days later,

on April 19th, after fifty- five days on hunger-strike, Sean McNeela

died. The hunger-strike ended that night when the prisoners were

informed that their demands had been met. In fact, those concessions

that were made were very short-, lived. Many of the prisoners on

short sentences were interned after completion of their sentences,

and those awaiting trial were given savage sentences.

With

the Second World War in progress at the time, the Free State premier

Eamonn de Valera, had ample excuse for imposing draconian censorship

and the compliant press drew little attention* to the deaths of

republicans at the hands of Fianna Fail. Tony D'Arcy, who left a

wife, two sons and baby daughter, was buried in his native Headford

in County Galway, and Sean McNeela's remains were taken to Ballycroy

in County Mayo. On January 21st 1942, another republican life was

claimed as a result of a hunger- strike when Belfast IRA Volunteer

Joseph Malone died after an operation on his stomach. Malone was in

jail in England for his part in the 1939 bombing campaign and had

been ill and in constant pain since taking part in a hunger-strike

the previous year. His. remains were brought home to Belfast where

he was given a hero's funeral in Milltown cemetery.

The last hunger-striker to die in a Free State jail is also often

remembered as a Belfastman. But, in fact, Sean McCaughey, who died

on May 11th 1946, spent the first five years of his life in

Aughnacloy, County Tyrone, before the family moved to Belfast in

1921. Sean McCaughey joined the IRA while still in his teens in

1934, and at the same time was closely involved in Gaelic League and

GAA activities. In 1938, he was on the Belfast IRA Staff, and in

1940, after a six-month spell imprisoned in the Free State, became

O/C of the IRA's Northern Command. A year later he was

Adjutant-General of the IRA when the then Chief-of-Staff, Stephen

Hayes, was held by the IRA as an informer. McCaughey was arrested in

Dublin, charged with 'common assault and the unlawful imprisonment'

of Hayes, and sentenced to death by a Free State military tribunal

in September 1941. This sentence was commuted to penal servitude for

life. During the forties, republican prisoners in the Curragh

internment camp. Arbour Hill and Mountjoy, were allowed to wear

their own clothes. But those transferred to* .Portlaoise were

expected to wear prison uniform, which they refused to do. McCaughey

was transferred to Portlaoise from the condemned cell at Mountjoy

and joined the other prisoners in refusing to wear prison clothes.

He spent the next four and three- quarter years naked except for a

prison blanket.

From September 1941, until the summer of 1943, McCaughey and his

comrades were kept in complete solitary confinement." The cell on

each side of them were kept vacant to ensure no communication, and

they were not allowed to leave their cells, even to use the

lavatory. After some considerable outside pressure, deValera

conceded minor concessions, in 1943, by allowing one hour's

exercise, morning and afternoon on weekdays, one newspaper each

week, and one letter in and out per month. Attempts, often brutal,

were still made to force the prisoners to wear prison uniform.

General prison conditions continued to be atrocious; and, in fact,

it was only a few. days before Sean McCaughey's death that he was

allowed his first visitor. McCaughey began his hunger-strike on

April 19th 1946. Five days later he intensified it by going on

thirst strike. From then until his death, he endured seventeen days

of the most excruciating torture which totally wrecked his body

before he eventually died on May 11th. Sean McCaughey's inquest

brought to the public eye, at last, the conditions which the

prisoners had been enduring for so long. The prison doctor admitted

at the inquest that he would not keep a dog in the conditions in

which Sean McCaughey had existed for four years and nine months. A

strong amnesty movement began to grow. At nightfall on Saturday 11th

May, McCaughey's remains arrived at the Franciscan Church on

Merchant's Quay, Dublin, from Portlaoise where the brown-clad friars

of St. Francis received it. The following morning after Requiem

Mass, McCaughey's remains were accompanied through Dublin by

thousands, whilst thousands more lined the route. He was buried in

Milltown cemetery, Belfast, the resting place of so many heroic

republicans before and since.

back to top

Take me home to Mayo ---

the 70s

By Patrick McGlynn

The previous four parts of this five- part series,

Patrick McGlynn

has

detailed the deaths of nine republican prisoners whilst on

hunger-strike, from Thomas Ashe in 1917 to Sean McCaughey in 1946.

During that period another eight men died, after hunger-strikes had

ended, but as a direct result of having taken part in a prison fast.

In this concluding article, the hunger-strike deaths, of Michael

Gaughan and Frank Stagg during the seventies, are recalled, bringing

the grim toll of this long rejection of criminalisation by Irish

republican prisoners up to the current tragic events in the H-Blocks

of Long Kesh.

Both the hunger-strike deaths of the seventies took place in

prisons in England. The first, on Monday 3rd June 1974, was Michael

Gaughan of Ballina, County Mayo, followed almost two years later by

another Mayo man, Frank Stagg of Hollymount, on Thursday 12th

February 1976. Michael Gaughan was one of the earliest IRA

Volunteers to be imprisoned in England in this phase of the

struggle, being sentenced to seven years at the Old Bailey in

London, in December 1971, for his part in a bank raid. He spent the

first two years of his prison sentence in Wormwood Scrubs in London

and then was moved to the Isle of Wight's top security prisons

first, Albany, and then, in 1974, to Parkhurst. Among the other

Irish political prisoners there at that time was Frank Stagg,

sentenced with other IRA Volunteers in Coventry the previous

November, to ten years' imprisonment, on the vacuous charge of

conspiracy to cause explosions.

November 1973 had also seen the trial in Winchester of the Belfast

Ten, Dolores and Marion Price, Hugh Feeney, Gerard Kelly and six

others, who had been arrested following bomb explosions in London

the previous March. Having received life sentences, the Price

sisters, Feeney and Kelly immediately began a hunger-strike for

repatriation to prison in Ireland. They were brutally force-fed for

a total of two hundred and six days. Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg

joined this hunger-strike on March 31st 1974, first of all in

solidarity with the other hunger-strikers and also for the right to

wear their own clothes and not to do prison work. On April 22nd,

twenty-three days into their hunger-strike, Gaughan and Stagg were

force-fed for the first time. They immediately escalated their

demand to one for repatriation. "The mental agony of waiting to be

force- fed is getting to the stage where it now outweighs the

physical discomfort of having to go through with it," one of the

hunger- strikers wrote to a relative. But the physical discomfort of

force-feeding was considerable. During the operation, the prisoners

were seated on a chair, and held down by the shoulders and chin. A

lever was pushed between the teeth to prise open the jaw and a

wooden clamp placed in the mouth to keep it open. A thick greased

tube was then put through a hole in the clamp, pushed down the

throat and into the stomach. Often the tube would go into the wind

pipe and have to be withdrawn. During this procedure the victim

would be constantly vomiting.

Visitors to Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg were only allowed to see

them through a glass screen, supervised by prison warders. In fact,

Michael Gaughan's last visit with his mother, three days before his

death, took place in such circumstances. Because the prisoners were

being force- fed, Michael Gaughan's death, on Monday 3rd June 1974,

came as a shock. He died from pneumonia; the force-feeding tube

having pierced his lung. He was twenty- four years of age.

The death of Michael Gaughan caused a major controversy in British

medical circles and the use of forced-feeding was later abandoned by

the British. More immediately, the four Belfast hunger-strikers were

promised repatriation and ended their hunger strike on June 7th;

Frank Stagg, having received a similar undertaking ended his fast

ten days later.

From the Isle of Wight to Ballina, Michael Gaughan's funeral

brought thousands on to the streets. On Friday 7th June and Saturday

8th June, thousands of people lined the streets of Kilburn in London

and marched behind his coffin, which was flanked by an IRA guard of

honour. On Saturday, his remains were met by thousands more in

Dublin and, flanked by IRA Volunteers again, were brought to the

Franciscan church on Merchant's Quay. On Sunday morning, the cortege

began the long journey to Ballina, stopping in almost every town and

village en route, as the people turned out to pay their last

respects. In Ballina, there was a Requiem Mass at the Cathedral. As

the coffin was borne outside, a volley of shots was fired over it,

before it was taken to Leigue cemetery, to be buried with full

honours in the republican plot.

A month after the death of Michael Gaughan, Frank Stagg was moved

from Parkhurst to Longlartin in Worcestershire. There, on October

10th 1974, Frank Stagg once more resorted to a hunger- strike,

because he had not been transferred to Ireland, and because he and

his relatives were being subjected to degrading searches before and

after visits. As soon as Frank Stagg began this hunger- strike all

his visits were stopped, although his mother was allowed a brief

visit on October 26th. Thirty-one days into the hunger-strike, he

was told that his demand for repatriation would be met and he ended

his hunger-strike. In March 1975, Dolores and Marian Price were

transferred to Armagh jail and, in April, Hugh Feeney and Gerard

Kelly were moved to the cages of Long Kesh. But Frank Stagg remained

in prison in England. By this time he was in Wakefield, where he was

being kept in solitary confinement because he refused to do prison

work. On December 14th 1975, Frank Stagg went on hunger-strike once

again. His demands were for an end to solitary confinement and no

prison work pending transfer to a prison in Ireland. This time any

promises from the authorities would have to be given in writing.

On January 20th 1976 Frank Stagg was given the Last Rites, but, the

following Sunday, the Bishop of Leeds ordered the prison chaplain

not to say Mass in the presence of Frank Stagg. In spite of this,

and much other pressure, Frank remained committed to his principles

and, after fasting for sixty-two days, died on February 12th 1976.

In order that he receive a republican funeral, Frank, before he

died, specified in his will that his body be entrusted to Derek

Highstead, the then Sinn Fein organiser in England. The Wakefield

coroner complied with this request. The remains of Frank Stagg were

on the way to Dublin by air, when the Free State government, to

prevent a display of republican sentiment like that which

accompanied the funeral of Michael Gaughan, diverted the plane to

Shannon airport.

Free State Special Branch men seized the coffin and locked it in the

airport mortuary, preventing relatives from gaining access. The

following day the coffin was transferred by helicopter to Robeen

church at Hollymount in County Mayo. On Saturday 2N1st February, a

Requiem Mass, boycotted by almost all his relatives, was held, and

his body was taken to Ballina, where it was borne by Special

Branchmen to a grave some yards from the republican plot in Leigue

cemetery where he had asked to be buried. In the hope of preventing

a transfer, six feet of cement was afterwards placed on top of the

coffin. On the Sunday, the Republican Movement held its ceremonies

at the republican plot. A volley of shots was fired and a pledge

made that Frank Stagg's body would be moved to the republican plot

in accordance with his wishes. For six months there was a permanent

twenty-four hour garda presence in Leigue cemetery, but eventually

it was lifted. On the night of November 6th 1976, a group of IRA

Volunteers, accompanied by a priest, dug down, beside the grave,

tunnelled under the cement and removed the coffin. After a short

religious service they re-interred the remains of Frank Stagg in the

republican plot, beside the remains of Michael Gaughan.

back to top

First Hunger

Striker Named: Bobby Sands

In a

statement smuggled out of the H-Blocks of Long Kesh, the first Irish

political prisoner to begin the hunger strike was identified as

Bobby Sands. Sands was the officer in charge during the pendency of

the last hunger strike and was one of the recipients of the

concessions which were broken by the British. The hunger strike

began at 12:01 AM on March 1 st, which was 7:00 PM EST Saturday the

28th of February. The prisoners' grave action has been forced upon

them in order to end systematic torture by the British and to gain

recognition of political prisoner status as constituted by the five

basic demands of no prison uniform, no penal work, educational

facilities and free association, a weekly visit, parcel and letter,

and restoration of remission. In making the announcement, Irish

political prisoners noted that they could not comply with the

request of the Republican Movement to forego a hunger strike at this

time.

Since

March 1st, 1976, the British have refused to recognize political

prisoner status for those held under political offenses hr the north

of Ireland. Those charged after that time were directed to wear a

criminal uniform symbolizing for British propaganda purposes that

they were "criminals and terrorists" rather than political

prisoners. Those arrested prior to that date will have the right to

wear their own . clothing and the other demands constituting

political status. In order to force criminalization, the British

have confined Irish political prisoners in the H-blocks of Long Kesh

naked except for a blanket in cells filled with human excrement,

without reading materials, access to other prisoners or a proper

diet. The prisoners are also routinely beaten. This systematic

torture led to the hunger strike between October 27th and December

18th and the failure of the British to abide by the concessions

given that night coupled with the reinstitution of these

psychological and physical torture techniques has forced the renewal

of the hunger strike as of Sunday, March 1st.

Meanwhile, in a joint statement issued by the political prisoners

in Long Kesh and Armagh British prisons, the prisoners announced

that in order to focus all attention on the issue of political

status and the hunger strike, commenced on Sunday, March 1,

1981 the prisoners would suspend the no- wash protest at this

time. The hunger strike to the death has been forced on the

prisoners because of the refusal by the British to restore

recognition o: political status and end systematic torture as agreed

on December 18,1981 at the close of

the last hunger strike.

The

full statement reads as follows: From Monday, March 2nd

1981, we the Republican political prisoners in the H Blocks

of Long Kesh and Armagh Prison, ' will be coming off the No Wash/ No

Slop Out Protest Exactly three years ago this month in the H Blocks

there commenced a period of intense harrassment by screws who

withdrew toilet and washing facilities in an attempt to break our

resistance by forcing us to live in the squalor of our own dirt It

developed as follows: If we went to the toilet we were assaulted so

we stayed in our own cells.

When

our chamber pots were full we were refused slop out buckets and it

was in this way that our cells first became dirty. When we smashed

the windows and threw the contents pf our chamber pots out the

windows we were hosed down and the windows were eventually all

boarded up. It was only after we had experienced all these

harrassments that we deliberately decided to turn their punishments

against them by making it into our own protest Like all attempts to

break our will their punishments failed and out of that

confrontation the 'No Wash/No Slop Out Protest emerged Similarly, in

February 1980 screws in Armagh, believing they were dealing with a

weak link in Republican resistance, withdrew toilet and washing

facilities and forced the Republican women onto a similar protest

However, with the hunger strike in the H Blocks now commanding

increasing attention we have decided to end the No Wash/No Slop Out

Protest and by doing so highlight the main areas of our demands

which are not about cell furniture or toilet facilities but about

the right not to wear prison uniform (prison issue clothing) in the

H Blocks, and in both the H Blocks and Armagh Prison the right not

to do prison work and the right to free association with fellow

political prisoners (which includes segregation from Loyalists).

Despite

ending the No Wash Protest and despite the public attention now

being focused on the prisons we do not expect the screws to react

more humanely. Each time we ring the bell to go to the toilet it

will % be at the whim of screws whether wejgot in which case we will

have to run a gauntlet of insults and assaults or don't go, in which

case the temptation out of frustration would be to return to the No

Wash Protest and a void all contact with the prison administration.

Nevertheless, as from today we are prepared to run that gauntlet to

highlight the hunger strike and the issue behind our demands for

political status. In the H Blocks the blanket protest, symbol of

Republican resistance, will continue, and in Armagh, where we the

women can already wear our own clothes, the No Work Protest will

also continue. Signed Pro, H Blocks Long Kesh, Pro Republican Women

Prisoners * Armagh Prison.

back to top

Bobby Sands

(1954 - 1981)

BOBBY

SANDS was born in Belfast on March 9th 1954. On his twenty-seventh

birthday, on Monday week, he will have been nine days on

hunger-strike in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh. Bobby joined the

Republican Movement when he was in his mid-teens, and when he was

eighteen he was arrested in Lisburn and charged with possessing four

handguns. Bobby was arrested with three others (Sean Lavery, Joe

McDonnell and Seamus Finucane) in a car in which one gun was

recovered. They were brought to Castlereagh and were interrogated

for six days and treated very badly. He refused to recognise the

court, and although the guns were in a very poor condition he was

sentenced to five years' imprisonment which he served as a political

prisoner in the cages of Long Kesh.

After his release, in April 1976, Bobby continued as an active

republican, and was re-arrested, six months later in October after

an IRA commercial bombing attack on the Balmoral Furnishing Company

in Upper Dunmurry Lane, near his Twinbrook home. When the RUC

arrived on the scene there was a gun battle, he and two of the other

Volunteers (Seamus Martin and Gabriel Corbett) were wounded and

apart from giving his name and address Bobby refused to answer any

questions. At the end of eleven months on remand, he and his five

comrades, who all refused to recognise the court, were sentenced in

September 1977. Despite them being caught in the vicinity of the

bomb attack, the judge had to admit that there was not enough

evidence to convict them on the explosives charge, but went on to

sentence four of them, including Bobby, to fourteen years'

imprisonment each, for possession of the same gun. As the trial came

to an end, a fracas started by prison warders broke out in court,

and as a result of this incident Bobby was sentenced to six months'

loss of remission.

He

spent the first twenty-two days of his sentence 'on the boards' in

Crumlin Road jail, fifteen days of which he was kept completely

naked and was ridiculed by the prison warders. When he was moved to

the H-Blocks in late September 1977, Bobby refused to wear a prison

uniform, and went on the blanket in resistance to the policy of

criminalisation. Later, under the pen-name, Marcella (his sister's

name), he began writing articles for 'Republican News'. In the

H-Blocks Bobby has suffered the routine abuse from the prison

administration and has been forcibly bathed and scrubbed down with

deck brushes a number of times. He was PRO of the blanket men in

the cages of Long Kesh in 1975 until he succeeded Brendan Hughes as

O/C when Brendan went on the hunger-strike in October. Bobby has

played a major part in formulating and leading republican resistance

to criminalisation within the Blocks, and recently conducted

negotiations with the prison governor, Stanley Hilditch, in

attempting to resolve the prison crisis, which foundered when the

British administration adopted an inflexible and intransigent

attitude. Bobby has now spent nearly eight years, including nine

successive Christmases, behind bars.

back to top

Rallies

in support for the hunger strikers begin

Irish

People -

Irish Northern Aid, N Y.

C, last Saturday March 21st. conducted the first in a series of

indoor rallies aimed at expressing the intensity of Irish-American

support for the Hunger Strikers. The rally combined representatives

from the media, politics, labor, various ethnic groups and

Irish-American organizations all of whom recorded their unqualified

support for the Irish hunger strikers in their demand for political

status and their determination to exert sufficient pressure upon the

British to see that Bobby Sands and his comrades do not die. The

purpose of the rally was stated as follows: Irish-Americans have

watched with concern , and our concern became indignation during the

hunger strike last winter and our indignation has become outrage.

We are here to express out- support for three basic principles:

1. That Englishmen

do not have a right to torture Irish men and women in order to

continue British rule in Ireland

2. That those Irish men

and women who resist British rule are political prisoners no matter

how many times Englishmen meet in Westminster and call them

criminals.

3. That Irish-Americans

are now determined to pressure Britain through our political

leaders, the media, Irish organizations, and the labor unions, to

see that Bobby Sands, Frankie Hughes, Raymond Mc Creesh and Patsy

O'Hara do not die in the infamous H-Blocks of Long Kesh prison on

the north of Ireland.

The initial spokesman,

Dr. Martin Abend, noted television commentator, stated that for him,

the hunger strike symbolized 800 years of Ireland's struggle. A few

against overwhelming force without weapons except their '

willingness to sacrifice their lives for the freedom of their

homeland will ultimately be victorious simply because they refuse to

be defeated.

Representatives of the

National Board of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Political

Education Committee, the Emerald Society of the Firefighters Union

and the New Jersey Irish Caucus then came to the microphone to

pledge their organizations fully to the cause of the hunger strike.

New York State Assemblyman Sean Patrick Walsh, who was instrumental

last winter in having a resolution passed by the New York State

Assembly calling for political status and an end to systematic

torture for Irish political prisoners, then spoke. He said that it

was pointless to examine the legal system or indeed the prison

system because as long as England rules Ireland, torture and

repression will rule Ireland.

Solidarity messages were

then read from United States Senator Alphonse D'Amato and

Congressional Representatives Leo Zefferetti and Geraldine Ferraro.

Zefferetti said, " British policy has failed miserably in

controlling the violence and in ensuring the rights of Ulsters

Nationalist population. It is clear that London's effort to impose a

military solution to a political problem is not the answer. The

people of Ireland must be given the opportunity to pursue their own

political destiny. The American people desire a just and lasting

peace for all of Ireland, and it is the duty and responsibility of

the United States government to use its influence in seeking that

peace."

Ferraro wrote, "I am

deeply concerned with the basic denial of civil and human rights

occurring in the north of Ireland. The callous deprivation of due

process, evidenced by the actions of the Diplock Courts, shows

little if any respect by the British judicial system for the

individual rights of Irish citizens. The time has come to set a new

peace initiative for all of Ireland that will put an end to the

gross violations of human rights occurring in Northern Ireland. It

is in the best interests of the United States that there be a just

and equitable solution to this problem in order that peace, order,

justice and well being be restored to to that part of the world."

D*Amato said, "The

struggle for human rights and dignity in Northern Ireland must be

supported by all freedom-loving people, injustice and religious

intolerance must be crushed and in its place a free and united

Ireland must be allowed to grow. I pledge my fullest support to all

the embattled people of Northern Ireland who seek to live in peace,

side by side, under the flag of a united Ireland."

Labor leaders Michael

Maye and Bill Tracey then spoke briefly, pledging their

organizations behind the hunger strikers. Longshoreman head, Teddy

Gleason. telegramed as follows: "I wish to express the concern and

support of the 100,000 members of the International Longshoreman's

Association, AFL-CIO, for the Irish political prisoners who are now

on hunger strike in Long Kesh prison in the north of Ireland. The

I. LA. has long opposed torture and tyranny by any government, and

we particularly support the Irish people for the reunification of

their country. . Again, We also urge all peoples who have an

interest and concern for the freedom and unification. of Ireland and

its people, and especially those interested in human rights,

dedicate themselves to making the Irish cause a moral issue in the

United States. It is time for meetings around the country to carry

out such an effort." Black political activist Amiri Baraka then

spoke stating that he was there as a foe of all imperialism,

particularly British imperialism in Ireland. Solidarity messages

were then extended by the American Indian Treaty Council and the

Welsh Socialist Republican MovemenL A second rally was announced for

Saturday, March 28, 1981 in San

Francisco. Meanwhile, 400 members of Irish Northern Aid picketed in

Philadelphia, including City Councilman Rafferty and the Mayor of

Upper Darby. A crowd of demonstrators also conducted a candlelight

vigil outside the British Consulate residence in Chicago.

back to top

Two more strikers named

The three were

interrogated at Bessbrook barracks, and three days later were

charged with attempting to kill British soldiers, conspiring to kill

British soldiers, possession of firearms, and IRA membership. After

nine months on remand Ray was sentenced m a non-jury court in March

1977. He refused to recognize the court. Next Tuesday he will have

been four years on the blanket, and during that time he has

forfeited his visits rather than wear the prison uniform for that

short half-hour per month. He took his first visit with his parents,

recently, to inform them that he was going on hunger-strike.

Patrick O'Hara was

born in Derry city on February 11 th 1957. He was only eleven years

of age when, along with his parents,' he took part in the big civil

rights march in Derry on October 5th,- 1968, which was batoned by

the RUC. A year later he again witnessed one of the milestones in

the present troubles when the RUC invaded, and were defeated, during

the Battle of the Bogside during August, 1969. Patrick, known as

Patsy, joined na Fianna h-Eireann in 1970 and although under-age,

he joined Sinn Fein in early 1971. A few months after the

introduction of internment his eldest brother Sean was interned.

One night as Patsy, then only fourteen years old was standing with

others manning a "no go' barricade in the Brandywell area, British

soldiers opened fire on them, wounding him in the foot. He spent

five weeks in hospital, being released shortly before Bloody Sunday,

January 30th, 1972. Later in the year he joined the Sticky

Republican Clubs but quickly became disillusioned with their

ignoring the national question. In 1974 his home was continually

raided by the British and he was frequently harassed and beaten up

by them, before being interned in October. After his release in

April 1975 he joined the Irish Republican Socialist Party, but

within two months he was re-arrested and framed by the British who

planted a stick of gelignite in his father's car, which he was

driving. He spent ten months on remand before being acquitted.

The British and RUC

continued to harass the O Hara family in 1976, and another brother.

Tony, who is now on the blanket in the H-Blocks. was arrested and

charged with a political offense for which he was subsequently

convicted on the basis of an alleged verbal statement. Patsy,

himself was arrested again in September 1976 and charged with

possessing arms and ammunition - this was really

internment-by-remand as he was released after four months when his

charges were dropped. In June 1977 he was arrested in Dublin,

interrogated for seven days, and charged with holding a garda at

gunpoint. He was released on bail six weeks later and in January

1978 he was acquitted. Patsy was arrested once more in May 1979. He

was charged with possession of a hand grenade and was convicted on

the basis of accusations made by two British soldiers. He was

sentenced to eight years imprisonment in January 1980 and

immediately went on the blanket.

back to top

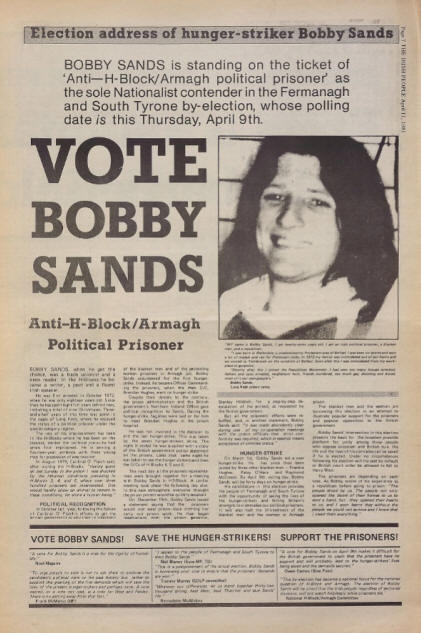

Sands stands for election

There will be an

election on the ninth of April in Ireland. Ostensibly, the election

will concern the parliamentary seat at Westminster, which was

vacated by the untimely death of Frank McGuire. Ostensibly the

election will concern the relative voter popularity as between the

two candidates. This election, literally, will not be like other

elections. This election will be a matter of life and death for one

of the contestants. For this election pits anti- H-block/ Armagh

candidate Bobby Sands against the Unionist Harry West. April 9th

will not just mark election day for Bobby Sands. It will mark his

fortieth day on hunger strike to the death, in his involuntary

campaign headquarters inside the H-block cells of Long Kesh prison.

HISTORICAL

The

tactic, is a traditional one in Irish history. Ireland's history

has been such, over the last eight centuries, that if one is to

compile a list of the nation's ten greatest men, it would reveal

asterisks next to most of the names bearing the legend imprisoned or

executed by the British. Given this history and given the British

penchant for a facade of democracy, allowing seats at Westminster

that were permanently overwhelmed by the number of British M.P.s who

govern Ireland in accordance with British financial interests rather

than in the interests of the Irish people, it is no mystery that one

of the earliest election slogans in Ireland might be "put him in to

get him out". The import of the slogan being that the Irish people

could use the British election machinery , to vote into Westminster

imprisoned Irish Republicans, thereby embarrassing the British

colonialists to release the "elected felon".

FAOI GLAS AG GALLAMH

The epitome occurred in the English general election of 1918.

Sinn Fein candidates pledged themselves, if elected to refuse to sit

at Westminster and to erect an Irish national assembly in Dublin.

Those calling for a free and united Ireland won an overwhelming

mandate from the Irish people of seventy-nine per cent of the vote.

Of the one hundred and five electoral seats which Britain allotted

Ireland, thirty-six had been won by Irish political prisoners. The

assembly or Dail was constituted in January 1919. As the roll was

called, those present responded "Faoi Glas ag Gallamh", (imprisoned

by the foreign enemy) when the names of the incarcerated Dail

members were read aloud. It is sad to note that had the electoral

will of the Irish people been adhered to by England rather than

being met with the response of partition and the Government of

Ireland Act, then there would be no war of national freedom in

Ireland, Bobby Sands would not be in prison and there would be no

Irishmen facing death on hunger strike in an English prison located

in Ireland.

MEANING

Once

again, as in 1918 the issue is clearly drawn. Harry West is a

Unionist, who is best known for his active role in the Ulster

Workers Council Strike, the Orange backlash against the hint of

concessions at Sunningdale. He is a prestigious figure among

Loyalists and an ardent advocate of continued British colonial rule

in Ireland with its institutionalized sectarian ascendancy in

employment, housing, and position before the state. A vote for him

is a vote of legitimacy for the six county state. Each vote for

Bobby Sands will convey a far different message. Sands serves a

fourteen year sentence in Long Kesh because of participation in the

struggle to end British colonial rule in Ireland. He is on hunger

strike to the death in order to affirm the right of the Irish people

to national freedom, the political right of those who are jailed for

resistance to British rule to be recognized as political prisoners

and his own individual right to be free from -torture and inhuman

treatment. Each vote for Bobby Sands shouts to the world that Sands

and his fellow blanketmen are recognized as heroes and patriots

rather than as criminals or terrorists by those for whose freedom

they fight. Each vote for Bobby Sands will be a shout of

determination that he shall not die in the infamous H-blocks of Long

Kesh. Each vote shouts ridicule upon the British, who may soon be

confronted with the decision as to whether they will force an

elected M.R to his death in Long Kesh prison.

back to top

The birth of a

republican - Bobby Sands

'The

birth of a Republican: from a nationalist ghetto to the battlefield

of H-Block', by hunger-striker Bobby Sands, was first published

anonymously in 'Republican. News', December 16th 1978. The

smuggled-out article, introduced as 'A blanket man recalls how the

spirit of republican defiance grew within him', is a

semi-autobiographical account. For example, although blanket men

have been denied compassionate parole for the funeral of a parent,

as described in the article, Bobby Sands' own mother was a the time

very much alive and, in fact, she had addressed the Belfast rally

held on the first day of his hunger- strike, calling for support for

her son to save his life.

CHILDHOOD

From my earliest days I

recall my mother speaking of the troubled times that occurred during

her childhood. Often, she spoke of internment on prison ships, of

gun attacks and death, and of early morning raids when one lay

listening with pounding heart to the heavy clattering of boots on

the cobble-stone streets, and as a new day broke, peeked carefully

out of the window to see a neighbour being taken away by the

Specials. Although I never really understood what internment was, or

who the Specials were, I grew to regard them as symbols of evil. Nor

could I understand when my mother spoke of Connolly and the 1916

Rising, and of how he and his comrades fought and were subsequently

executed — a fate suffered by so many Irish rebels in my mother's

stories. When the television arrived, my mother's stories were

replaced by what it had to offer. I became more confused as 'the

baddies' in my mother's tales were always my heroes on the TV. The

British army always fought for 'the right side' and the police were

always 'the good guys'.. Both were to be heroised and imitated in

childhood play.

SCHOOL

At

school I learnt history, but It was always English history and

English historical triumphs in Ireland and elsewhere. I often

wondered why I was never taught the history of my own country and

when my sister, a year younger than myself, began to learn the

Gaelic language at school I envied her. Occasionally, nearing the

end of my school days, I received a few scant lessons in Irish

history. For this, from the republican-minded teacher who taught me,

I was indeed grateful. I recall my mother also speaking of 'the good

old days'. But of all her marvelous stories I could never remember

any good times, and I often thought to myself 'thank God I was not a

boy in those times', because by then - having left school' - life to

me seemed enormous and wonderful. Starting work, although

frightening at first, became alright, especially with the reward at

the end of the week. Dances and clothes, girls and a few shillings

to spend, opened up a whole new world to me, I suppose at that time

I would have worked all week, as money seemed to matter more than

anything else.

CHANGE

Then

came 1968 and my life began to change. Gradually the news changed.

Regularly I noticed the Specials, whom I now knew to be the 'B'

Specials, attacking and baton-charging the crowds of people who all

of a sudden began marching on the streets. From the talk in the

house and my mother shaking her fist at the TV set, I knew that they

were our people who were on the receiving end. My sympathy and

feelings really became aroused after watching the scenes at

Burntollet. That imprinted itself in my mind like a scar, and for

the first time I took a real interest in what was going on. I became

angry. It was now 1969, and events moved faster as August hit our

area like a hurricane. The whole world exploded and my own little

world just crumbled around me. The TV did not have to tell the story

now, for it was on my own doorstep. Belfast was in flames, but it

was our districts, our humble homes, which were burnt. The Specials

came at the head of the RUC and Orange hordes, right into the heart

of our streets, burning, looting, shooting, and murdering. There was

no-one to save us, except 'the boys', as my father called the men

who defended our district with a handful of old guns. As the

unfamiliar sound of gunfire was still echoing, there soon appeared

alien figures, voices, and faces, in the form of armed British

soldiers on our streets. But no longer did I think of them as my

childhood 'good guys', for their presence alone caused food for

thought. Before I could work out the solution, it was answered for

me in the form of early morning raids and I remembered my mother's

stories of previous troubled times. For now my heart pounded at the

heavy clatter of the soldiers' boots in the early morning stillness

and I carefully peeked from behind the drawn curtains to watch the

neighbours' doors being kicked in, and the fathers and sons being

dragged out by the hair and being flung into the backs of sinister-

looking armoured cars. This was followed by blatant murder: the

shooting dead of our people on the streets in cold blood. The curfew

came and went, taking more of our people's lives.

IRA

Every

time I turned a corner I was met with the now all-too-familiar sight

of homes being wrecked and people being lifted. The city was in

uproar. Bombings began to become more regular, as did gun battles,

as 'the boys', the IRA, hit back at the Brits. The TV now showed

endless gun battles and bombings. The people had risen and were

fighting back, and my mother, in her newly found spirit of

resistance, hurled encouragement at the TV, shouting 'give it to

them boys!' Easter 1971 came, and the name on everyone's lips was

'the Provos', the people's army, the backbone of nationalist

resistance. I was now past my eighteenth year, and I was fed up with

rioting. No matter how much I tried,' or how many stones I threw I

could never beat them — the Brits always came back. . . . I had seen

too many homes wrecked, fathers and sons arrested, neighbours hurt,

friends murdered, and too much gas, shootings, and blood, most of it

my own people's.

At eighteen-and-a-half.

I joined the Provos. My mother wept with pride and fear as I went

out to meet and confront the imperial might of an empire with an M1

carbine and enough hate to topple the world. To my surprise, my

school- day friends and neighbours became my comrades in war. I soon

became much more .aware about the whole national liberation struggle

— as I came to regard what I used to term 'the troubles'.

OPERATIONS

Things

were not easy for a Volunteer in the Irish Republican Army. Already

I was being harassed, and twice I was lifted, questioned, and

brutalised, but I survived both of these trials. Then came another

hurricane: internment. Many of my comrades disappeared — interned.

Many of my innocent neighbours met the same fate. Others weren't so

lucky, they were just murdered. My life now centred around

sleepless nights and standbys, dodging the Brits, and calming nerves

to go out on operations. But the people stood by us. The people not

only opened the doors of their homes to us to lend a hand, but they

opened their hearts to us, and I soon learnt that without the people

we could not survive and I knew that I owed them everything. 1972

came, and I had spent what was to be my last Christmas at home for

quite a while. The Brits never let up. No mercy was shown, as was

testified by the atrocity of Bloody Sunday in Derry. But we

continued to fight back, as did my jailed comrades, who embarked

upon a long hunger-strike to gain recognition as political

prisoners. Political status was won just before the first, but

short-lived, truce of 1972. During this truce the IRA made ready and

braced itself for the forthcoming massive Operation Motorman,-which

came and went, taking with it the barricades. The liberation

struggle forged ahead, but then came personal disaster - I was

captured. It was the autumn of '72. I was charged, and for the first

time I faced jail. I was nineteen-and-a- half, but I had no

alternative than to face up to all the hardship that was before me.

Given the stark corruptness of the judicial system, I refused to

recognise the court. I ended up sentenced in a barbed wire cage,

where I spent three-and-a-half years as a prisoner-of-war with

'special category status'. I did not waste my time. I did not allow

the rigors of prison life to change my revolutionary determination

an inch. I educated and trained myself both in political and

military matters, as did my comrades. In 1976, when I was released,

I was not broken. In fact, I was more determined in the fight for

liberation. I reported back to my local IRA unit and threw myself

straight back in to the struggle. Quite a lot of things had changed.

Belfast had changed. Some parts of the ghettos had completely

disappeared, and others were in the process of being removed. The

war was still forging ahead, although tactics and strategy had

changed. At first I found it a little bit hard to adjust, but I

settled into the run of things and, at the grand old age of

twenty-three, I got married. Life wasn't bad, but there were still a

lot of things that had not changed, such as the presence of armed

British troops on our streets and the oppression of our people. The

liberation struggle was now seven years old, and had braved a second

and mistakenly- prolonged cease-fire. The British government was now

seeking to Ulsterise the war, which included the attempted

criminalisation of the IRA and attempted normalisation of the war

situation. The liberation struggle had to be kept going. Thus, six

months after my release, disaster fell a second time as I bombed my

way back into jail!

CAPTURE

With my wife being four

months pregnant, the shock of capture, the seven days of hell in

Castlereagh, a quick court appearance and remand, and the return to

a cold damp cell, nearly destroyed me. It took every ounce of the

revolutionary spirit left in me to stand up to it. Jail, although

not new to me, was really bad, worse than the first time. Things

had changed enormously since the withdrawal of political status.

Both republicans and loyalist prisoners were mixed in the same wing.

The greater part of each day was spent locked up in a cell. The

screws, many of whom I knew to be cowering cowards, now went in

gangs into the cells of republican prisoners to dish out unmerciful

beatings. This was to be the pattern all the way along the road to

criminalisation: torture, and more torture, to break our spirit of

resistance. I was meant to change from being a revolutionary freedom

fighter to a criminal at the stroke of a political pen, reinforced

by inhumanities of the most brutal nature. Already Kieran Nugent

and several more republican POWs had begun the blanket protest for

the restoration of political status. They refused to wear prison

garb or to do prison work. After many weekly remand court

appearances the time finally arrived, eleven months after my arrest,

and I was in a Diplock court. In two hours I was swiftly found

guilty, and my comrades and I were sentenced to fifteen years. Once

again I had refused to recognise the farcical judicial system. As

they led us from the courthouse, my mother, defiant as ever, stood

up in the gallery and shook the air with a cry of 'they'll never

break you, boys', and my wife, from somewhere behind her, with

tear-filled eyes, braved a smile of encouragement towards me. At

least, I thought, she has our child. Now that I was in jail, our

daughter would provide her with company and maybe help to ease the

loneliness which she knew only too well. The next day I became a

blanket man, and there I was, sitting on the cold floor, naked, with

only a blanket around me, in an empty cell.

H-BLOCKS

The

days were long and lonely. The sudden and total deprivation of such

basic human necessities as exercise and fresh air, association with

other people, my own clothes, and things like newspapers, radio,

cigarettes, books, and a host of other things, made life very hard.

At first, as always, I adapted. But, as time wore on, I came face to

face with an old friend, depression, which on many an occasion

consumed me and swallowed me into its darkest depths. From home,

only the occasion letter got past the prison censor. Gradually my

appearance and physical health began to change drastically. My eyes,

glassy, piercing, sunken, and surrounded by pale, yellowish skin,

were frightening. I had grown a beard, and, like my comrades, I

resembled a living corpse. The blinding migraine headaches, which

started off slowly, became a daily occurrence, and owing to no

exercise I became seized with muscular pains. In the H-Blocks,

beatings, long periods in the punishment cells, starvation diets,

and torture, were commonplace. March 20th, 1978, and we completed

the full circle of deprivation and suffering. As an attempt to

highlight our intolerable plight, we embarked upon a dirt strike,

refusing to wash, shower, clean out our cells, or empty the filthy

chamber pots in our cells. The H-Blocks became battlefields in which

the republican spirit of resistance met head-on all the inhumanities

that Britain' could perpetrate. Inevitably the lid of silence on the

H-Blocks blew sky high, revealing the atrocities inside. The

battlefield became worse: our cells turning into disease- infested

tombs with piles of decaying rubbish, and maggots, fleas and flies

becoming rampant. The continual nauseating stench of urine and the

stink of our bodies and cells made our surroundings resemble a

pigsty. The screws, keeping up the incessant torture, hosed us down,

sprayed us with strong disinfectant, ransacked our cells, forcibly

bathed us, and tortured us to the brink of insanity. Blood and tears

fell upon the battlefield — all of it ours. But we refused to yield.

PROUD

The

republican spirit prevailed and as I sit here in the same conditions

and the continuing torture in H-Block 5, I am proud, although

physically wrecked, mentally exhausted, and scarred deep with hatred

and anger. I am proud, because my comrades and I have met, fought

and repelled a monster, and we will continue to do so. We will never

allow ourselves to be criminalised, nor our people either.

Grief-stricken and oppressed, the men and women of no property have

risen. A risen people, marching in thousands on the streets in

defiance and rage at the imperial oppressor, the mass murderer, and

torturer. The spirit of Irish freedom in every single one of them —

and I am really proud. Last week, I had a visit from my wife,

standing by me to the end as ever. She barely recognised me in my

present condition and in tears she told me of the death of my dear

mother - God help her, how she suffered. I sat in tears as my wife

told me how my mother marched in her blanket, along with thousands,

for her son and his comrades, and for Ireland's freedom. When the

screws came to tell me that I was not getting out on compassionate

parole for my mother's funeral, I sat on the floor in the corner of

my cell and I thought of her in heaven, shaking her fist in her

typical defiance and rage at the merciless oppressors of her

country. I thought, too, of the young ones growing up now in a war-

torn situation, and, like my own daughter, without a father, without

peace, without a future, and under British oppression. Growing up to

end up in Crumlin Road jail, Castlereagh, barbed wire cages, Armagh

prison and Hell- Blocks. Having reflected on my own past I know this

will occur unless our country is rid of the perennial oppressor,

Britain. And I am ready to go out and destroy those who have made my

people suffer so much and so long. I was only a working class boy

from a nationalist ghetto, but it is repression that creates the

revolutionary spirit of freedom. I shall not settle until I achieve

the liberation of my country, until Ireland becomes a sovereign

independent socialist republic. We, the risen people, shall turn

tragedy into triumph. We shall bear forth a nation!

back to top

New Jersey Indoor Rally:

The

fifth in a series of National Hunger Strike Defense Rallies

organized by Irish Northern Aid took place Sunday, April 12th,

1981, in New Jersey at Seton Hall University. The rally was

chaired by Peter Farley of the Irish National Caucus of New Jersey

Inc. who stated that the rally was intended as a showing of support

for the hunger strikers. He then introduced the first speaker, Fr.

Kevin Flanagan. Fr. Flanagan talked about the impact which

Irish-American support exerted in British calculations as to whether

they would drive Irish political prisoners to their deaths, rather

than stop attempting to impose criminalization by systematic

torture. The next speaker was television commentator Dr. Martin

Abend, who noted that attempts have been made to censor or silence

him because of his Republican stand on Ireland. Abend noted that the

British seem to particularly fear him because he is of a non- Irish

ethnic background. He stated that years ago he had seen that as

long as the British ruled Ireland as long as the British ruled a

part of Ireland, it would mean torture, political prisoners, state

encouragement of sectarianism and warfare. Everything that has

occurred during the last ten years has reinforced his analysis. He

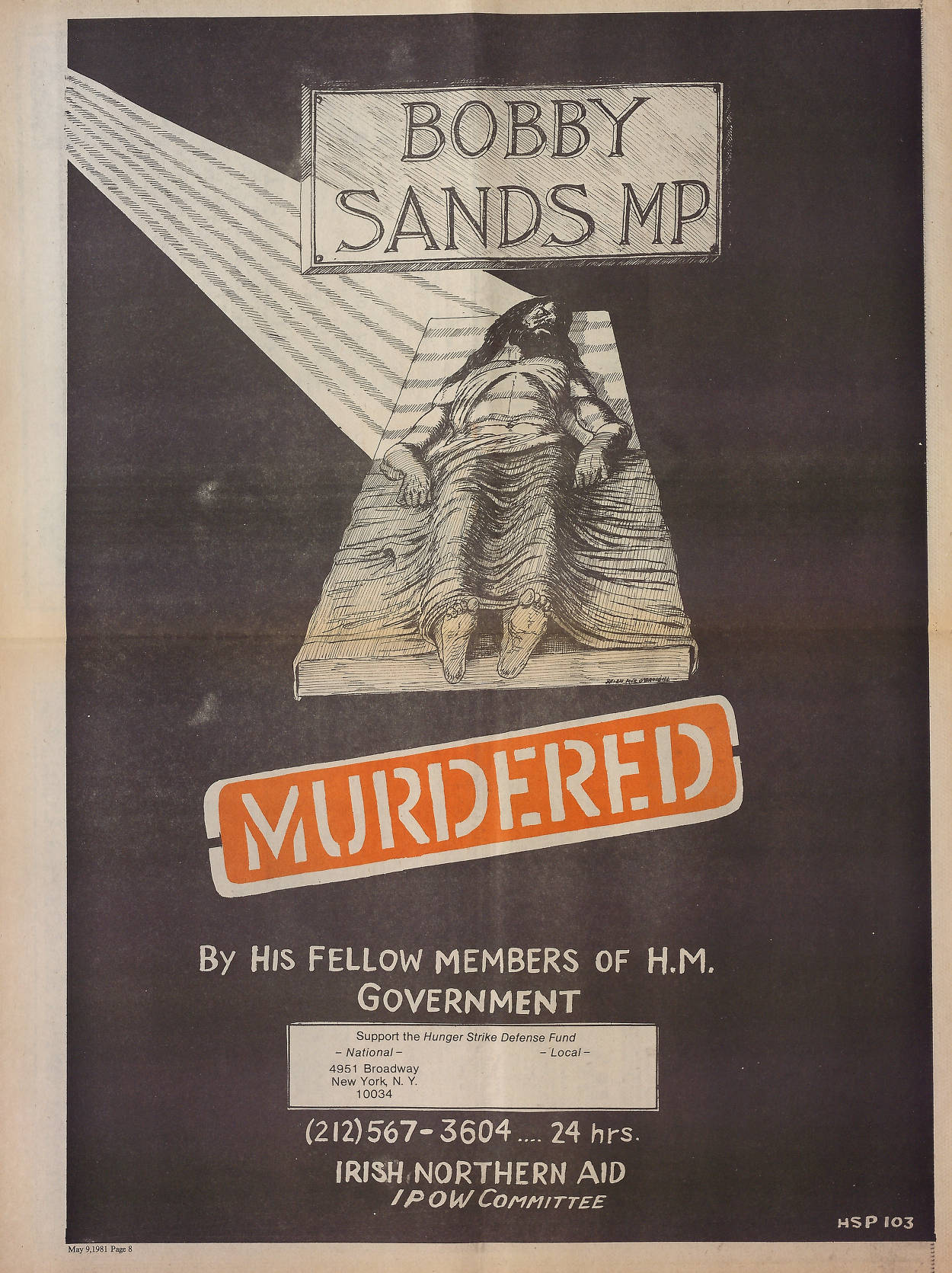

added that the hunger strike itself, with an elected member of

Parliament dying on hunger strike in a British jail, is but one more

manifestation of the evil done by the partitioning of Ireland.

Dr.

Abend was followed by Martin Galvin of Irish Northern Aid. Mr.

Galvin spoke about the implications of Bobby Sands' election victory

stating that, "The Britons have stood at Westminster and called

those who resist British colonial rule in Ireland criminals and

terrorists, but the Irish people have again thrown the lie back in

their faces and shouted to the world that Ireland regards those who

resist British colonial rule in Ireland as patriots and freedom

fighters." Mr. Galvin then read a telexed statement from Sands which

responded to reports that he will be expelled from Westminster.

Galvin noted "Such an expulsion will prove even more conclusively

than the election result, if that is possible, the basic point which

Sands sought to make - that so long as Britain rules a part of

Ireland the will of the Irish people will mean nothing and British

interests will mean everything in determining the government of the

country."

The

next speaker was unannounced It was former blanketman Seamus Delaney

of Belfast Delaney detailed his case, in which he was convicted on

the basis of a confession beaten out of him after four days at

Tennent Street Barracks which left 27 marks on his body. He was

sentenced to 31 years, and but for the intervention of Dr. Robert

Irvin, the. police surgeon who examined him, he would still be

confined in the infamous H- Blocks of Long Kesh rather than having

his case accepted .by the European Court at Strasbourg. He noted

that such cases are typical and went on to describe the inhuman

conditions of the blocks. The next speaker was State Senator

Patrick Dodd of New Jersey. Dodd stated that he was personally

gratified at Sands election victory, which showed- how the people

are behind the political prisoners. He alluded to the apparently

imminent attempt to expel Sands and stated that no matter what

course the British pursued they would not overcome the implications

of Sands victory. The next speaker was also an elected official New

Jersey Freeholder Francis Fahy, who spoke on behalf of the Political

Education Committee of the Ancient Order of Hibernians. He placed

himself personally and his organization solidly behind the hunger

strikers and the blanketmen. The closing speaker was Michael

Costello of the Irish Northern Aid Prisoner of War Committee. Mr.

Costello spoke of the urgency of American support and outlined a

number of activities and demonstrations which will take place in the

immediate future.

back to top

Sands' Victory!

The

election is over. The people of South Tyrone and Fermanagh have

spoken Bobby Sands has won. It was an unexpected triumph.

Supportive realists and pragmatists had hoped for a Sands vote of

fifteen thousand, which would have provided a solid show of popular

support. Optimists had hoped for twenty to twenty-five thousand

votes as a tremendous showing in the face of the overt opposition of

the Loyalist candidate and the covert opposition of the Social

Democratic and Labor Party (SDLP) which had called for the voting of

blank ballots. The victory which emerged was unforeseen and indeed

mind- boggling in light of such opposition. It is even now

impossible to grasp all of the implications and ramifications of

that victory won by the young blanketman on his forty-first day of

hunger strike to the death. It is, however, readily apparent that it

is a victory of enormous magnitude whose impact will not only be

felt by the British, but also by politicians in the Irish Free State

and in America itself. The

election is over. The people of South Tyrone and Fermanagh have

spoken Bobby Sands has won. It was an unexpected triumph.

Supportive realists and pragmatists had hoped for a Sands vote of

fifteen thousand, which would have provided a solid show of popular

support. Optimists had hoped for twenty to twenty-five thousand

votes as a tremendous showing in the face of the overt opposition of

the Loyalist candidate and the covert opposition of the Social

Democratic and Labor Party (SDLP) which had called for the voting of

blank ballots. The victory which emerged was unforeseen and indeed

mind- boggling in light of such opposition. It is even now

impossible to grasp all of the implications and ramifications of

that victory won by the young blanketman on his forty-first day of